Quantitative Data Shows that Listening to Complex Drumming can Increase Attention.

Several years ago we created a Continuous Performance Test (CPT) to see if listening to complex drumming rhythms can improve focused attention.

We created this test to follow-up on two independent studies showing that REI drumming can increase focused attention. One study compared BSR music to the AD/HD stimulant medication, Ritalin, using a Continuous Performance Test (the T.O.V.A.) for an adult with Attention Deficit Disorder while the other study used a blinded placebo-controlled format for elementary-age children in a classroom setting.

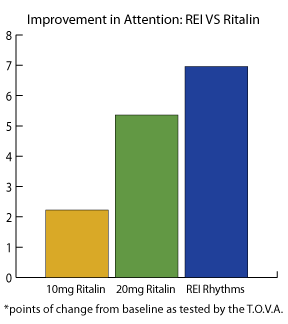

Complex REI Drumming Beats Ritalin for Sustaining Attention in an Adult with ADD

This study (1) compared BSR’s music to two different doses of the ADD stimulant medication, Ritalin (10mg and 20mg). Using quantitative measures of scores from the Test of Variables of Attention (T.O.V.A.), four conditions were examined: Baseline (no meds or music), 10mg of Ritalin taken 90 minutes before the test, 20mg of Ritalin taken 90 minutes before the test, and while listening to REI music rhythms.

The subject’s baseline score was -12.74, putting him squarely in the AD/HD camp (anything below a score of 0.00 suggests attention problems).

His score with 10mg of Ritalin was a slightly improved -6.60 while his 20mg Ritalin score showed a significant improvement with a score of -3.47.

His score when listening to the REI focusing music, the same tracks you will find in the Focus category of Brain Shift Radio, were a near normal score of -1.87.

This improvement was nearly 50% greater than the better of the Ritalin scores.

These results suggest that REI offers a strong alternative to Ritalin (and other stimulant medications used for ADD).

The advantages of BSR music include an absence of side-effects, individual customization to achieve the optimal stimulation level for each person, and improved sustained attention.

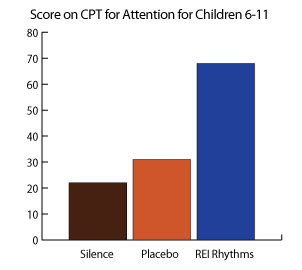

REI Drumming Improves Concentration in Elementary School Children

This study (2) examined 100 elementary-aged children in a double-blind, placebo-controlled format. Students performed four separate CPTs (Continuous Performance Tests), consisting of two tests with no music and two tests with either a placebo music recording or REI music tracks. Children were randomly assigned to the placebo or REI test group.

The results showed a significant improvement in attention for those who listened to the REI recording over both the silence and placebo conditions. The silence group produced an average score of 23, the placebo group scored at 31, and the REI Rhythm group scored an average of 68.

These results have been encouraging enough that Brain Shift Radio has invested tremendous time and energy developing a next-level study to further explore the efficacy of REI rhythms and the delivery of BSR music.

BSR’s Attention Tests Move Music Research a Step Forward

With Brain Shift Radio’s Continuous Performance Test we are moving music research forward by conducting the largest study ever done on music for focusing.

Our attention tests were built using standardized, quantitative testing methods on an expanding platform which will allow us to collect and analyze limitless data with a goal of using this data to not only determine whether music can improve focused attention but also which techniques offer the most significant results for each population group.

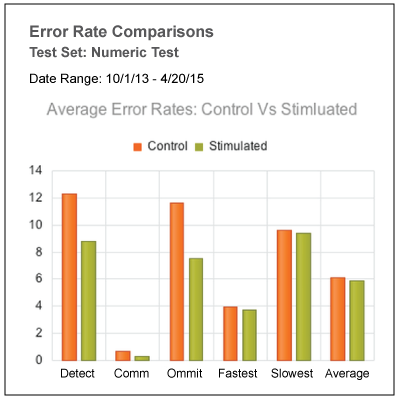

Thousands of Tests = Some amazing results

Since we launched the BSR CPT initiative thousands of people have taken the test. The results we’ve seen are 3.6 times better than the most popular study on music for cognition (and the number of people who have taken our test is hundreds of times more than this study) (3).

As an overview, the average error-rate reduction was 36.73% with improvements falling fairly consistently across the three error types.

These are significant numbers and suggests that listening to Brain Shift Radio when you need to focus may help you sustain your attention.

We saw reductions in all three error rates – detection, commission and omission – with the BSR music (stimulated) condition compared to the silence (control) condition.

Detection errors (Detect): The silence (control) condition error rate was 12.42. The BSR music (stimulated) condition showed an error rate of 8.69. This is a 3.73 or 30.0% reduction of errors.

Commission errors (Comm): The silence (control) condition error rate was .73. The BSR music (stimulated) condition showed an error rate of .39. This is a .34 or 46.5% reduction of errors.

Omission errors: The silence (control) condition error rate was 11.58. The BSR music (stimulated) condition showed an error rate of 7.67. This is a 3.91 or 33.7% reduction of errors.

Fastest click: For the silence (control) condition the fastest click speed was 383 ms. The BSR music (stimulated) condition showed an average click speed of 355 ms (milliseconds). This is a 28 ms or 7.3% slower click-time.

Slowest click: For the silence (control) condition the slowest click speed was 968 ms. The BSR music (stimulated) condition showed an average click speed of 932 ms. This is a 36ms or 3.7% faster click-time.

Average click: Of the three click speeds the average offers us the best data. For the silence (control) condition the average click speed was 608 ms. The BSR music (stimulated) condition showed an average click speed of 579 ms. This is a 31 ms or 5.1% faster click-time.

Note: Data used for these studies are anonymous and complies with IRB and HIPAA requirements for client privacy and research integrity.

Sources:

1. A Study for Improved Concentration by Acoustic Drum Rhythms Music Medicine Therapy

2. REI Rhythms Beat Ritalin for Adult with Attention Deficit Disorder